Deviation investigation guidelines in the pharmaceutical industry

- Kazi

- Last modified: March 13, 2025

Deviations in the pharmaceutical industry are so common and potentially destructive to the business that you cannot afford not to manage them properly.

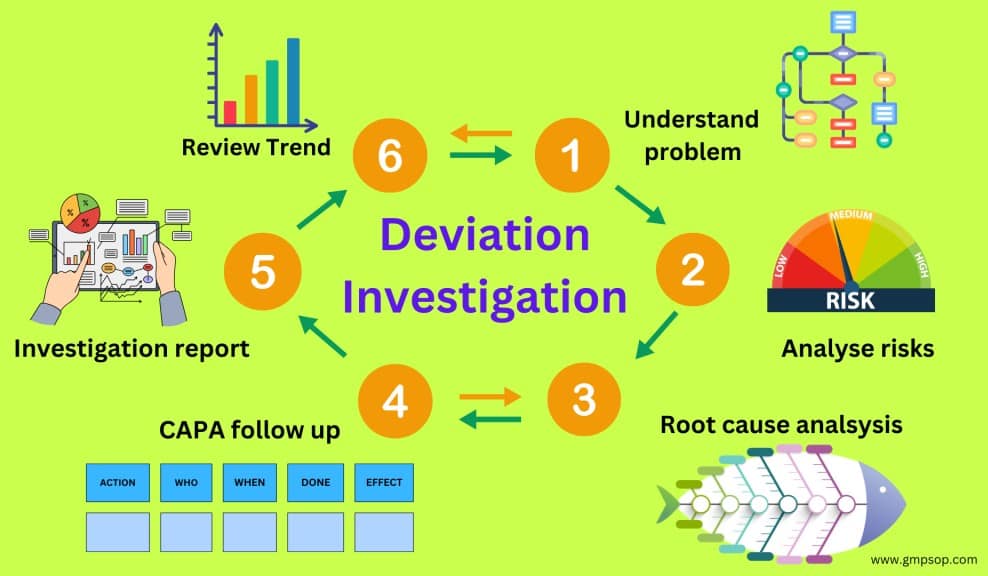

The deviation investigation process is the key to managing all critical and major deviations.

A long time ago, my professor explained deviation to me using two examples.

Imagine you are driving a car. As you speed, the tyres will come into constant friction with the road. Friction will create force in the opposite direction. If not controlled, it can push the car out of the lane.

The steering wheel is your control. If you firmly hold it, the car will stay on its path.

Another good example of deviation is the rocket launch and how it reaches its destination. At the time of ignition at the launcher, immense thrust is produced to maneuver the spacecraft.

At this point, the rocket faces countless errors from chemical and mechanical reactions. Any of these, if not controlled, can cause the rocket to deviate from its path.

As the rocket propels from point A to point B, it is never a straight path. Its inertial guidance mechanism constantly measures how much it has deviated from the trajectory. A navigational system can accurately measure those deviations.

The rocket can always correct its trajectory by firing one or more thrust motors in opposite directions. The rocket reaches its destination by constantly measuring deviations and corrections.

From a quality management system perspective, deviations are unintentional errors. They must be managed (i.e., reported, investigated, and corrected) to remove detrimental impacts on the products.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Deviations are unexpected events that do not comply with standard procedures and can impact product quality, safety, or system integrity. They may arise from human error, machine malfunctions, or environmental issues. Addressing deviations requires thorough investigation, proper documentation, and implementing corrective and preventive actions to ensure GMP compliance and prevent recurrence.

- Deviations are either planned or unplanned. Planned deviations are intentional, controlled changes for improvement that require prior assessment and approval. Unplanned deviations are unexpected incidents requiring immediate reporting, investigation, and corrective actions. Planned deviations are proactive; unplanned deviations are reactive.

- Some familiar sources of unplanned deviations in pharmaceuticals include production issues during manufacturing, EHS hazards, environmental monitoring failures, material complaints, audit findings, validation discrepancies, housekeeping non-conformance, and customer complaints. Each requires appropriate action to ensure quality and compliance.

- Deviation reporting is the first step in managing deviations. Everyone must promptly report deviations using a standardised procedure, whether paper-based or electronic. Deviations impacting quality, specifications, or procedures require investigation and corrective action, unlike general events that do not affect product quality.

- Initial deviation reports should include key details such as the deviation number, priority, dates, reporter, title, brief description, and immediate corrective actions. Clear reporting ensures consistent investigation and resolution.

- After the initial report, quality assurance assesses its risk and classifies it as minor, major, or critical based on its impact on product quality, patient safety, and compliance. This classification is derived from a risk matrix where severity and likelihood are evaluated. Risk-based deviation classification facilitates the planning of corrective actions. Minor deviations require corrections, while major and critical deviations necessitate in-depth investigations and corrective measures.

- A systematic deviation investigation is necessary when the root cause is unclear, trends repeat, or significant quality risks are evident. The investigation should methodically identify causes and implement corrective and preventive actions to prevent recurrence.

- Popular tools for deviation investigation include fishbone diagrams (cause-and-effect), spider diagrams, Pareto charts, histograms, and brainstorming.

- Fishbone analysis, a cause-and-effect diagram, involves five steps: defining the problem, mapping the process, analysing causes, evaluating solutions, and implementing controls.

- After completing a deviation investigation, file all supporting records, reports, and remedial actions. Minor deviations may be logged in GMP records, while critical or major ones require detailed reports, including root cause analysis, corrective actions, and approvals.

- Planned deviations need a justification, impact assessment, and quality assurance approval before implementation.

- An unplanned deviation investigation aims to identify CAPAs that prevent recurrence. A clear SOP should guide CAPA implementation, tracking, and periodic effectiveness review.

- In deviation management, trend analysis is important to spot adverse patterns, refine actions, reduce repeat deviations, and drive continuous improvement.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

What is deviation?

A deviation is a departure from standard operating procedures or specifications resulting in non-conforming materials and processes.

Deviations are unusual or unexplained events that can potentially impact product quality, system integrity, or personal safety.

Deviation can occur due to human errors, incorrect instruction, environmental factors, machine malfunctions, etc.

For example, you may have accidentally added incorrect raw materials to the blend that are not in the bill of materials (BOM) or product specification. This can be classified as a deviation. After a thorough investigation, you may reject the whole blend or rework if possible.

Another deviation example can be printing an incorrect batch number on the cartons. After an investigation, you may be able to save the products through rework and repackage with the correct batch number while separating and destroying the bad cartons.

There is no limitation on the scenarios where deviation can occur on the production floor. Therefore, one can conclude when things do not go according to plan, they almost always result in deviations.

To comply with GMP, these deviations must be recorded in real-time and investigated with appropriate tools (e.g., root cause analysis).

Corrective and preventative actions should be implemented to avoid the recurrence of the deviation.

What is the purpose of a deviation investigation in GMP?

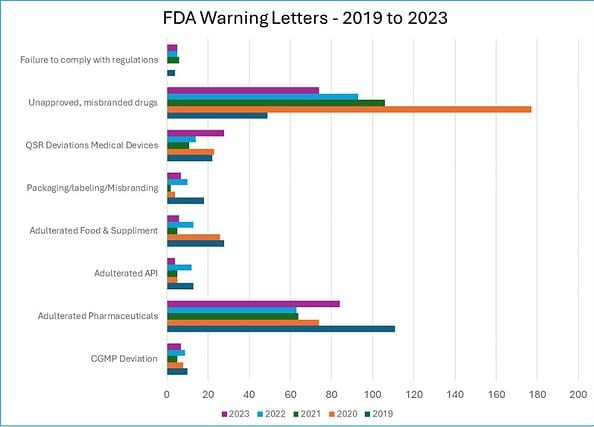

The importance of deviation investigation in the pharmaceutical industry can be reflected in the following statistics.

The FDA issues numerous warning letters to companies yearly for violating regulatory expectations. Many of those are direct results of ineffective or no-deviation investigations.

In the five years between 2019 and 2023, the FDA issued the following warning letters, which were closely related to ineffective deviation investigations.

i. CGMP Deviation: 39 warnings

ii. Adulterated Pharmaceuticals: 396 warnings

iii. Adulterated API: 39 warnings

iv. Adulterated Food & Supplements: 78 warnings

v. Packaging/labelling/Misbranding: 41 warnings

vi. QSR Deviations Medical Devices: 98 warnings

vii. Unapproved, misbranded drugs: 499 warnings

viii. Failure to comply with regulations: 20 warnings

Source: FDA Warning Letters

The charts below show that cGMP Deviations were the largest (26%) category of warning letters in 2019.

In 2019 and 2020, warning letters were issued for “Adulterated Food and Supplements” at 36% and 33%, respectively.

Failure to comply with regulations was the biggest (30%) reason for warning letters in 2021.

Similarly, the packaging, labelling, and misbranding-related warning letters were the top reasons in 2019.

I want to point out that not all warning letters can be directly attributed to deviation investigation failure.

However, the warning letters’ titles suggest that the impacted businesses could have significantly reduced those numbers through adequate deviation management.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

Different types of deviations in pharmaceuticals

There are two types of deviations. Planned and unplanned.

Planned deviations are those you raise to improve a process or system. You must take necessary measures to control the impact of planned deviation so it does not adversely impact your product or system.

Unplanned deviations are incidental, and you would not have any prior knowledge of the incident.

Unplanned deviations require a lot more effort to mitigate the risks, especially if the impact on the product is detrimental.

This article will explore more elements of unplanned deviations than planned deviations.

1. Planned deviation

A planned deviation is required when a process needs to be purposefully deviated from an operational SOP or a specific batch of products, process, or formulation.

Planned deviations are predefined, time-bound, and can be measured. A planned deviation is only considered as an exception. Not a norm.

You must have a system that can log and track all planned deviations.

A planned deviation must be assessed and approved by the requesting department and the quality assurance before implementation.

A proposal for planned deviation should cover the following aspects:

– It must be compliant with GMP and regulatory expectations.

– It must be assessed for risk to products and processes.

– Impact assessment should be stretched to other products.

– Market assessment as part of the deviation management process.

– All stakeholders, including third parties, should be notified and allowed to assess the impact on their areas before implementing planned deviation.

– Rationale for continuous improvement of a process or quality management systems.

2. Unplanned deviations

Unplanned deviations may occur at any manufacturing stage, such as dispensing, processing, testing, packaging, holding, or storage.

The deviation may result from system failure, equipment malfunction, or human error. As soon as an unplanned deviation is detected, all employees must report it to their Supervisor so corrections can be made before it gets out of control.

Departmental subject matter experts should complete a deviation investigation into the incident to assess the potential impact on product quality, purity, or strength.

The fundamental difference between a planned and unplanned deviation is that the planned deviation is raised intentionally to improve a system, while the unplanned deviations are unexpected events or incidents.

Common sources of deviations in pharmaceuticals

An unplanned deviation would not have occurred in the first place if you had foreseen its existence.

Therefore, you cannot limit the number of situations that may lead to deviation.

However, based on common knowledge, we can categorize deviations based on their source and where the deviations are observed:

i. Production deviation: This usually occurs during the manufacturing of a pharmaceutical batch. If not rectified on time, these can lead to product complaints.

ii. EHS deviation: This is raised due to the identification of “EHS Hazard.”

iii. Environmental Monitoring deviation: These are raised when you experience results that are out of specification derived from environmental monitoring tests.

iv. Material complaint: raised to document any issues regarding non-conforming, superseded, or obsolete raw materials/components, packaging, or imported finished goods

v. Audit deviation: Raised to flag non-conformance identified during internal, external, supplier, or corporate audits.

vi. Technical deviation: These can be raised for validation discrepancies, i.e., manufacturing instruction modification.

vii. Housekeeping deviation: Raised due to non-conformance of a housekeeping audit.

viii. System routing deviation: Raised to track changes made to the Bill of Materials (BOM) due to an Artwork change. These deviations are usually planned.

ix. Quality improvement deviation: This is a planned deviation. This may be raised if a potential weakness is identified in the quality system.

x. Customer complaint deviation: This is raised to investigate and track customer complaints of specific products and batches released. If the complaints are persistent, they may reflect a fault in the manufacturing process or formulation. In the worst case, it could result in a market recall.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

How to report an unplanned deviation?

Deviation reporting is the first step of any deviation investigation workflow.

It is important to understand that everyone in the pharmaceutical manufacturing facility is responsible for reporting a deviation as soon as one is identified.

You should have an established procedure for reporting and investigating deviations, ensuring a consistent approach to reporting and investigating deviations.

As soon as a deviation is detected from established methods, manufacturing documents, products or material specifications, etc., you must report the deviation using a paper-based or electronic reporting form.

Deviation from the standard operating procedure or confirmed out-of-specification results must be reported using the same approach.

All batch production deviations (planned or unplanned) in all manufacturing facilities, equipment, operations, distribution, procedures, systems, and record-keeping must be reported and investigated for corrective and preventative action.

In this case, clearly distinguishing an event from a deviation is important.

An event does not directly impact product quality; hence, it should not be treated as seriously as a deviation.

A deviation should be reported if a trend of discrepancies is noticed that requires further investigation.

A deviation report may or may not require an investigation. The report should contain the following information:

– A unique deviation number from the register.

– Priority of the deviation.

– Date deviation identified.

– Date deviation reported.

– Person reporting deviation.

– Deviation title.

– Provide a short description of the deviation, including location, process, approximately what and when the deviation was observed, etc.

– What immediate corrective actions were taken to prevent it from expanding?

In the later section, we will explore how to write a deviation investigation report.

How to assess a reported deviation for further investigation?

After a deviation is reported, quality assurance usually assesses it and assigns a level or category.

This assessment period is called the preliminary investigation stage.

During the assessment, quality assurance assesses overall risk by examining the following aspects of the deviation:

– Scope of the deviation. For instance, batch affected (both in-process and previously released).

– Trends relating to similar products, materials, equipment and testing processes, product complaints, previous deviations, annual product reviews, returned goods, etc, where appropriate.

– A review of similar causes.

– Potential quality impact.

– Impact on Regulatory commitment.

– Other batches potentially affected.

– Market actions (i.e., recall, etc.)

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

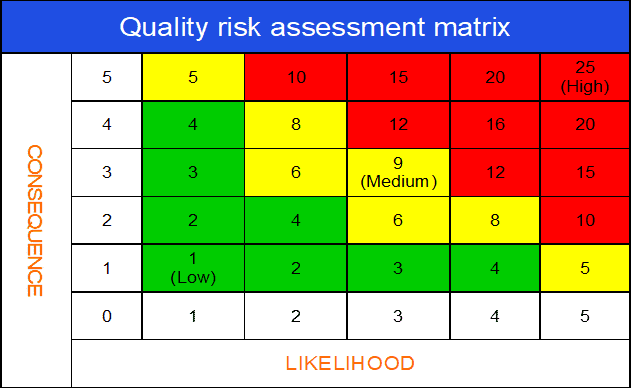

a. Assess different levels of deviation risks

To assess risk more easily, any deviation can be classified into one of three levels, 1, 2, and 3, based on product impact and seriousness.

Level 1: Minor deviation (shaded by green color on the risk matrix below)

If you detect a deviation that is less serious or isolated and does not impact product quality and safety, it is deemed a minor deviation.

Minor deviations are not critical or major but require correction or suggestions on improving systems or procedures that may be compliant but would benefit from the improvement (e.g., incorrect data entry).

Example: An incorrectly spelt product name on the manufacturing instructions can be classified as a minor deviation. It is likely to be caused by human error or another isolated event. It does not directly impact product quality but must be corrected immediately.

Level 2: Major deviation (shaded by yellow color on the risk matrix below)

When you detect a deviation from company standards or current regulatory expectations that has the potential to significantly risk product quality, patient safety, or data integrity, this is categorized as a major deviation.

Major deviation could also result from significant observations from a regulatory agency or a combination/repetition of “other” deficiencies that indicate system failure (s).

Example: During the online check of a packaging line, the QA inspector found that a superseded version of the leaflet insert was used in the pack. This deviation does not directly impact product quality (as the defect was discovered on the line) but adversely impacts good manufacturing practices.

Moreover, the defect was identified before the batch was released to market. Hence, it can be corrected through reworking the batch.

Level 3: Critical deviation (shaded by red color on the risk matrix below)

Deviation from company standards or current regulatory expectations that provide an immediate and significant risk to product quality, patient safety, or data integrity.

A serious deviation can be escalated to a critical level due to a combination or repetition of unresolved major deficiencies that indicate a critical failure of systems.

Example: A confirmed assay result indicated a consistent shortage of active ingredients in the finished product.

This is a critical deviation since the medicinal batch does not comply with the label claim (strength) and violates regulatory expectations.

b. Use of quality risk matrix in deviation investigation

The quality risk assessment matrix is arguably the most important segment of the deviation risk evaluation process.

The risk matrix is very useful for visually expressing the impact of a deviation on product quality and GMP. Also, you can assess how likely the deviation would cause harm to product quality.

By assessing the severity and likelihood of impact together, you can create an overall deviation risk profile (e.g., critical, major, or minor).

A deviation risk matrix can be depicted in the following diagram.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

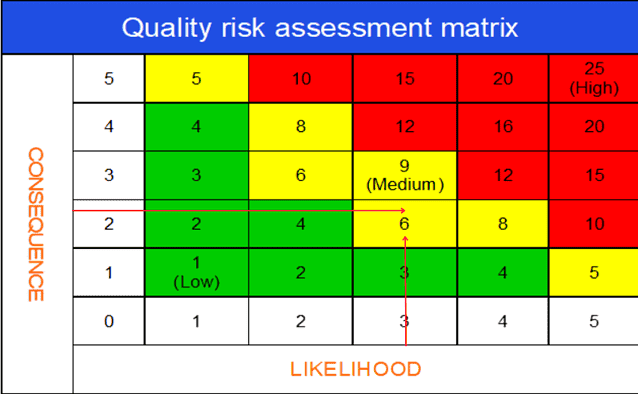

An example of risk assessment in deviation investigation

Consider a single incident that has taken place at your workplace that was categorized as an unplanned deviation.

After the initial deviation report, QA performs a risk assessment to classify whether the deviation is critical (L3), major (L2), or minor (L1).

Following is the way you might do it.

Consequence (Severity – product quality / GMP impact) scoring scale:

1 – No impact on the quality

2 – Minor quality impact

3 – Major quality impact

4 – Critical quality compromised

5 – Risk for customer or production outside regulatory expectations

Likelihood (Probability) scoring scale:

While assessing the Likelihood (probability), it is a good idea to consider the existing controls in place and the relative detectability of the incident through those controls.

1 – No chance of occurrence

2 – Chance of occurrence is remote

3 – Occurrence is unlikely

4 – Occurrence is probable

5 – Occurrence is definite

Overall risk score: Severity X Probability

The tool can also be used for analysing a manufacturing process to identify high risk steps / critical parameters.

Risk threshold interpretation:

Risk score (1-4): Low Risk. No specific action is necessary to close the investigation.

Risk score (5-9): Medium Risk. Some actions may be necessary to control the assessed risks.

Risk score (10-25): Medium to High Risk. Product quality risk is medium to high. Failure to take appropriate action could lead to product rejection or recall.

After an initial assessment of the deviation, the team agreed to assign,

– 2, as the score for consequence (impact of product quality and GMP) and

– 3, for Likelihood (probability that the deviation will occur again).

Now multiply the ratings for both variables.

The result 3 x 2 = 6 will indicate the deviation has a major (L2) risk profile.

c. Decide if a deviation investigation is necessary

A deviation investigation is required once a deviation is classified as critical or major.

Deviation investigation is a systematic approach to defining, measuring, and analyzing a deviation to identify the root cause of an incident.

Once the root cause is known, corrective and preventive action should be implemented to prevent the deviation from reoccurring.

A deviation investigation is necessary if one or more of the following criteria are met:

i. The deviation is critical or major in nature (Levels 3 and 2) according to the deviation risk profile.

ii. You cannot immediately identify the root cause of the deviation, or the cause is obscure.

iii. The available evidence shows a probable cause, but the cause is not confirmed.

iv. A deviation demonstrates repeated trends or repeated complaints.

Your organization’s quality team should set up a cross-functional investigation (CFI) meeting with all relevant parties as soon as possible.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

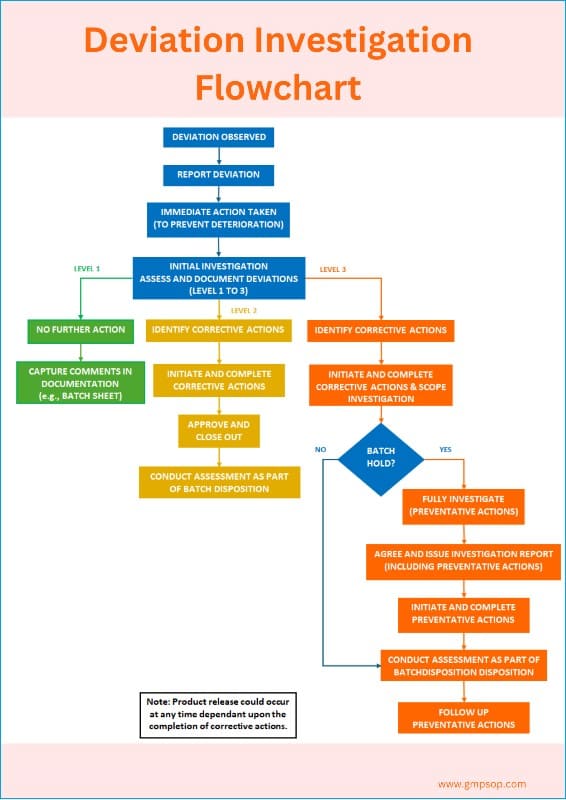

What is a deviation management flowchart?

A deviation management flowchart can be used as a decision tree. It serves as a visual aid depicting the complete lifecycle of deviation management.

An example of a deviation investigation flowchart shows how to report a deviation, assess the deviation profile, and when to conduct an investigation.

What are the tools used to investigate deviation?

The main objective of deviation investigation is to identify the root cause of an incident.

You may like to use the following tools while conducting a deviation investigation.

i. Fishbone diagram

ii. Spider diagram

iii. Pareto chats

iv. Histograms

v. Brainstorming

While the investigation approaches differ slightly from tool to tool, the fundamentals remain the same.

Irrespective of the tool you choose, the ultimate success will be correctly identifying the root cause and assigning corrective and preventive action to prevent the recurrence of the deviation.

How is deviation investigation (root cause analysis) done?

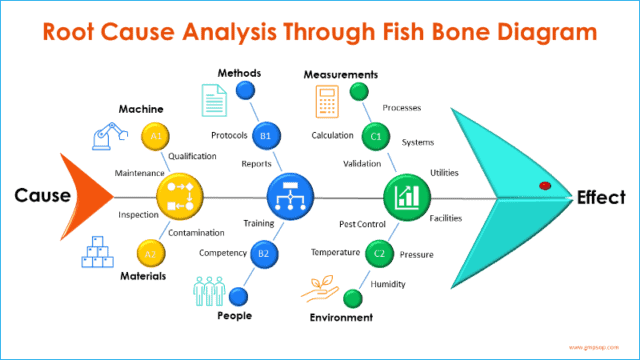

Fishbone (diagram) analysis is one of the most popular and widely used tools for root cause investigation.

It is also called a Cause-and-Effect diagram, as the process starts from the mouth of the fish (the Effect) and seeks to identify the exact root causes that have resulted in or contributed to the effect.

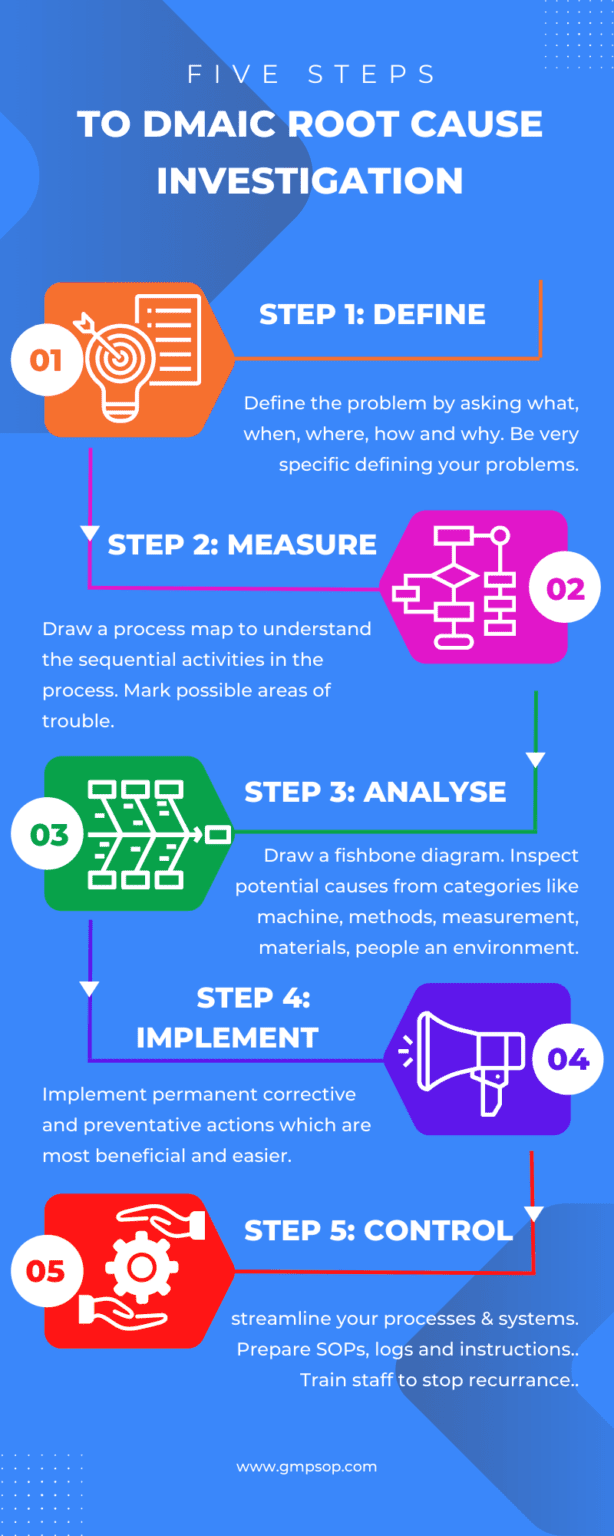

The root cause investigation process follows a sequential five-step question-and-answer pattern.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

Step 1: Define (problem definition)

This is the first section of the root cause investigation.

The section has questions to help participants define the problem, its history, and any previous work.

Typical questions during the defining stage are:

– What is the problem/incident? (record exactly what happened).

– When did it happen? (record the date and time of the incident).

– Where did it happen? (to record what process, equipment, or facilities were impacted).

– Who was working when the incident was discovered? (record who had found the incident the first time).

– What actions are taken immediately to fix the problem? (to record briefly the actions taken and by whom?).

– How long did it take to fix the problems? (to determine incident lost time).

– Has this happened before? (to identify history or trends on similar incidents).

– What actions were taken before? (to record any changes made previously).

Step 2: Measure (understanding the process)

At this step, the subject matter experts draw a detailed process map on a piece of paper to understand the sequential activities involved in the process within which the incident was discovered.

As the outline of the process map is complete, the participants attempt to mark possible areas of weakness where the deviation/incident has occurred.

A simple process mapping example for incoming goods release may involve sequentially:

– Receipt of new batch of raw materials.

– Reconciliation between requisition and packing slip.

– Decision – If both (requisition and picking slip) do not match, reject the material.

– If both match, store the material in a quarantine cage

– Samples are taken for QC testing

– Decision – testing does not pass – reject the lot.

– Test result passes specifications – accept the lot.

– QA review the Certificate of Analysis (C of A).

– Decision – C of A does not meet internal specification – reject the lot; or

– C of A meets internal specifications – approve the lot

– Release for further processing, etc.

During the exercise, participants try to mark possible areas of concern on the process map that may be responsible for repeat incidents and are worth analyzing more in-depth.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

Step 3a: Analysis (process analysis)

This step is designed to determine whether significant changes to the process might have contributed to repetitive incidents. The participants must also identify and list the process controls and possible non-value-adding steps.

Step 3b: Analysis (root cause analysis)

This section is designed to perform a cause-and-effect analysis using a fishbone diagram (also known as Ishikawa diagrams).

The process starts by adding the effect (defined problem) at the front of the fish head and creating branches of possible causes from the six process areas and systems.

Participants brainstorm on each of six broad categories or systems, which are:

– Machine

– Methods

– Measurements

– Materials

– People, and

– Environments

Step 3c: Analysis (5 WHYs, Pareto Chart)

In this step, the participants pick the possible causes of the problem marked on the Fishbone diagram.

Each potential cause is then spread down by asking “WHY” on five successive occasions or until the participants feel the best possible root cause has already been attained.

You should brainstorm all the possible causes of the problem. Ask, “Why does this happen?” As each idea is given, a branch (bone) is drawn from the appropriate category.

Causes can be written in several places if they relate to several categories. Again asks, “Why does this happen?” about each cause. Write sub-causes by branching off the cause branches.

It continues to ask “Why?” and generate deeper levels of causes, continuing to organize them under related causes or categories.

This will help you identify and address root causes to prevent future problems.

If found beneficial, a Pareto analysis can be done separately to show the fewest (20%) most significant causes, which have been causing the highest (80%) level of effects.

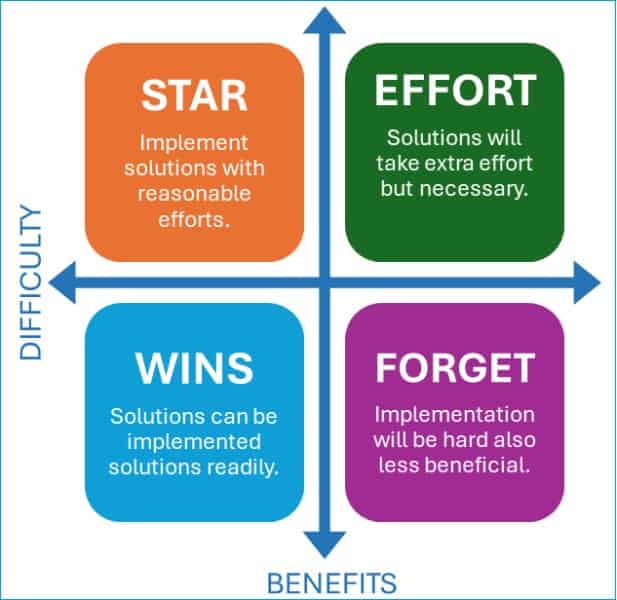

Step 4: Improve (Evaluate solutions)

Each solution is placed within a matrix as the solutions are identified in the analysis step 3c. The solutions are grouped into four possible placements within the matrix, which are:

i. Stars (High benefit, Low difficulty)

These solutions should be implemented with reasonable efforts, which can contribute highly to stopping the recurrence of the incident.

ii. Quick Wins (Low benefit, Low difficulty)

These solutions should be implemented readily, which may contribute to stopping the recurring incidents.

iii. Extra Effort needed (High benefit, High difficulty)

These solutions are relatively hard and lengthy to implement. However, once implemented, these can effectively prevent such incidents.

iv. Forget It (Low benefit, High difficulty)

These solutions are perceivably the least effective but harder to implement. These possible solutions can be discarded.

Step 5: Control (Implement solutions)

This final step involves listing the most effective and reasonable action controls to be implemented to improve the problem areas.

If a system or process change is necessary, raise a change request and assess the potential impacts of those changes on the system or process.

Then, streamline all documentation to reflect the change permanently.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

How to write a deviation investigation report?

After the deviation investigation is completed, you will need to keep all electronic or paper records used to support the investigation, together with a record of the investigation report (if applicable) and remedial action taken.

a. Unplanned deviation reporting checklist

The degree of documentation required may vary according to the level of the deviation.

For example, minor deviations can be recorded in batch or other GMP documentation, whereas more significant deviations (critical or major) are usually recorded using a specific proforma.

Batch-related deviations must be referenced or filed with the relevant batch records.

The following minimum requirements must be included in the unplanned deviation investigation documentation, as appropriate:

Deviation investigation reporting requirements | Applicable levels | ||

Minor | Major | Critical | |

Description of the incident, including date and time of occurrence, date of discovery, and the person who found the incident. | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Product, including product code and batches, is directly impacted. | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Description of immediate corrective action taken | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Initial QA assessment of seriousness (may change after the investigation starts). | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Definition of scope (for example, other batches and products potentially impacted). | – | Yes | Yes |

Definition of any appropriate additional actions (corrective and preventative actions). | – | Yes | Yes |

Documented investigation findings. | – | Yes | Yes |

The conclusion of the investigation, including the cause and any decision on batch disposition. | – | Yes | Yes |

Formal quality assessment and approval. | – | Yes | Yes |

A tracking system for deviations and corrective and preventative actions must be implemented. | – | Yes | Yes |

A more in-depth investigation is needed, including rigorous root cause analysis. | – | – | Yes |

Identification of preventative actions to prevent recurrence. | – | – | Yes |

Consider any wider impact of the deviation (for example, other sites or third-party sites). | – | – | Yes |

When you prepare the report for an unplanned deviation that requires a cross-functional investigation, you should include the following:

– Deviation report number

– Description, date, and time of the event or occurrence.

– Identification of the material or product involved, including lot numbers or system.

– Identify the master production documents involved and their current effective dates.

– Investigation details, including review of relevant quality systems, test data (when applicable), control charts (where applicable), and all lot(s) potentially affected.

– Supporting rationale(s) for the root cause of the deviation. If the cause is:

i. The cause is readily assignable to deviation

ii. The cause is probable with supporting evidence but unconfirmed; or

iii. Cause is undetermined, and the conclusion is summarized without speculation as to cause.

– Final decision regarding the batch disposition (i.e., rework, reject, release, etc.)

– List all corrective and preventative actions with assigned responsibilities and target completion dates.

– Approvals by all involved in the investigation

b. Planned deviation reporting checklist

You should include the following element in a planned or temporary deviation report:

– Deviation report number.

– Identification of the material or product involved, including lot numbers or systems.

– Rationale justifying the deviation plan and assessing the impact on product quality and validated state.

– Final approval of the rationale and the plan, including any follow-up, by the quality assurance.

– All planned deviation investigations must be approved before implementation.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

What is the difference between deviation and CAPA?

Deviations are unexpected incidents that result from a departure from standard procedures, processes, and systems that may adversely impact the product.

Depending on the deviation risks, each type of deviation is managed uniquely.

Minor deviations do not require investigation and may be managed through one-off corrective action or suggestion.

On the contrary, critical and major deviations should be investigated properly to assign the root cause.

The corrective and preventative actions are the results of the deviation investigation process.

Once the root cause is identified clearly, you must establish a list of CAPAs and assign that responsibility to individuals with a timeline for implementation.

How to manage CAPA after deviation investigation?

The expected outcome from an unplanned deviation investigation is a list of corrective and preventative actions that should effectively stop the recurrence of the deviation in the future.

You should establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) for implementing CAPA and a tracking mechanism for effectiveness over time.

The CAPA SOP must include the following:

– Provide a clear description of the deviation requiring correction.

– The deviation investigation that determines the action to be taken.

– Timelines for closure.

– Person responsible for implementing CAPA.

– CAPA implementation approvals.

– Details of the resolution.

– Effectiveness check

– Tracking mechanism to ensure all items are addressed

A systematic approach for trending of deviations

Repeat deviations are a significant headache for any pharmaceutical plant.

A deviation investigation may seem successful as we believe the root cause was identified accurately and the CAPA campaign was effective.

However, some incidents are seasonal, which could mask the real problem. After investigation, the deviation may not have occurred for some time, although the root cause and CAPA were inaccurate.

That is why a periodic review of CAPA effectiveness and trending deviation is essential to deviation management.

In addition to assigning specific actions through individual deviation investigations, you should conduct periodic reviews of all deviations to help identify trends and define improvement actions where appropriate.

Trending of deviations provides valuable insights into a larger problem that can help you to establish key performance indicators (KPIs) against which success can be measured.

Effective trend analysis can help eliminate specific types of deviations and ongoing improvement in deviation performance.

It can result in a reduction in the number of deviations and the elimination of repeat deviations.

250 SOPs, 197 GMP Manuals, 64 Templates, 30 Training modules, 167 Forms. Additional documents are included each month. All written and updated by GMP experts. Check out sample previews. Access to exclusive content for an affordable fee.

Conclusion

Deviation is an unexpected departure from a process, procedure, or specification that can adversely impact product quality and regulatory compliance.

Neglecting obvious deviations can be extremely detrimental to product safety and to pharmaceutical businesses. Ineffective deviation investigations are one of the main reasons for the FDA’s warning letters each year.

There are two types of Deviations: planned and unplanned. This article mainly explored the management practices of unplanned deviation and the investigational approach to unplanned deviations.

Proactive deviation reporting is the first step of any deviation investigation workflow. Everyone in the pharmaceutical manufacturing facility is responsible for reporting a deviation as soon as one is identified.

After the initial reporting, all deviations must undergo a thorough risk assessment. This step is crucial as it helps determine the severity of the deviation, whether minor, major, or critical, and dictates the necessary actions.

Minor deviations are less severe or isolated and do not impact product quality and safety. Hence, they do not warrant an investigation and root-cause analysis. A one-off correction is usually sufficient.

On the contrary, the critical and major deviations must be investigated at different intensities to determine assignable causes and subsequent corrective and preventive actions.

Fishbone diagrams (cause-and-effect analysis), Pareto analysis, histograms, and brainstorming are some of the popular deviation investigation tools used by pharmaceutical companies.

Irrespective of the tool you would prefer to use, the goal is to correctly identify the root cause and assign corrective and preventive action to prevent the recurrence of the deviation.

It’s important to be aware of the common causes of deviations. Human errors, random isolated incidents, incorrect instruction, processing errors, laboratory testing errors, environmental factors, machine malfunctions, etc., are some of the common assignable causes.

To complete an investigation report, you must follow a clear process. The best practice is to use a decision tree and documentation checklist while preparing the report as supporting evidence.

Author: Kazi Hasan

Kazi is a seasoned pharmaceutical industry professional with over 20 years of experience specializing in production operations, quality management, and process validation.

Kazi has worked with several global pharmaceutical companies to streamline production processes, ensure product quality, and validate operations complying with international regulatory standards and best practices.

Kazi holds several pharmaceutical industry certifications including post-graduate degrees in Engineering Management and Business Administration.

Thanks I have just been looking for information about this subject for a long time and yours is the best Ive discovered till now.